In his piece, The Footnote: A Curious History, Anthony Grafton explores the illustrious life stirring at the bottom of the page in much academic history writing. He begins this history of historiography recognizing the role of the footnote in legitimating the professional historian and slowly becoming a stale routine (4-5). As my colleagues have finished or continue to finish their dissertations, it has remained exceedingly clear that the genre demands careful attention to the performance at the bottom of the page. The dissertation marks expertise and admission to the professional guild, so as Grafton suggests, it makes great sense that footnoting would be a critical part of the dissertating endeavor (4). By the end of his “curious history,” Grafton highlights that footnotes are an indication of the inevitable selectivity of all writing and betray the conversational nature of history (233-34).

In his piece, The Footnote: A Curious History, Anthony Grafton explores the illustrious life stirring at the bottom of the page in much academic history writing. He begins this history of historiography recognizing the role of the footnote in legitimating the professional historian and slowly becoming a stale routine (4-5). As my colleagues have finished or continue to finish their dissertations, it has remained exceedingly clear that the genre demands careful attention to the performance at the bottom of the page. The dissertation marks expertise and admission to the professional guild, so as Grafton suggests, it makes great sense that footnoting would be a critical part of the dissertating endeavor (4). By the end of his “curious history,” Grafton highlights that footnotes are an indication of the inevitable selectivity of all writing and betray the conversational nature of history (233-34).

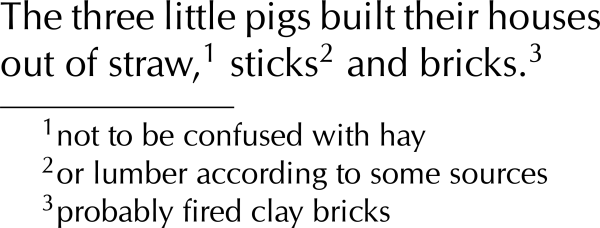

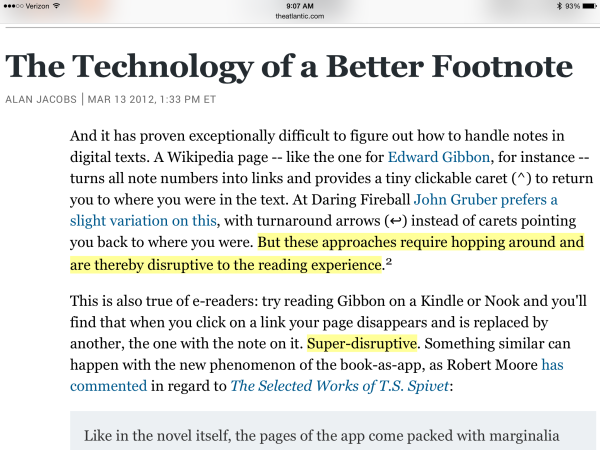

Yet, footnotes, notes at the foot of the page, strike me as indefinitely bound to the print medium. If I hope to make a dissertation in a medium otherwise than print, what would footnotes look like? Should they remain? Can we simply use hyperlinking to offer a digitized version of the footnote, with linked anchors quickly moving a reader from text body to notes and back? Are there ways in which this digitized footnote begins to blur the line between footnote and endnote? Do our digital and mobile book and reading media suggest a new kind of marginalia rather than the notable vestiges of the print codex? In his 2012 Atlantic piece, “The Technology of a Better Footnote,” Alan Jacobs points out the difficulty of mediating footnotes in the growing e-reader and internet reading landscape. His concern seems to be the problematic tendency in hypertextual technologies toward disrupting the reading experience (note his own use of standard footnotes in this article).

Clearly, I sympathize with Jacobs as I struggle to find my own practice of the relationship between body and margin in these otherwise-than-print media. Yet, for me, disruption is constitutive of the reading process. So, rather than asking how technology can smooth out the reading experience, I wonder how we might practice new media in ways that foreground disruption as a vehicle toward attention not simply a mode of distraction.

Clearly, I sympathize with Jacobs as I struggle to find my own practice of the relationship between body and margin in these otherwise-than-print media. Yet, for me, disruption is constitutive of the reading process. So, rather than asking how technology can smooth out the reading experience, I wonder how we might practice new media in ways that foreground disruption as a vehicle toward attention not simply a mode of distraction.

With an unlimited or flexible page length on the web, could the conversations that were once relegated (perhaps relegated is too pejorative a term? it could be that this space at the margin is a privileged space, a space where there are fewer restrictions on what can be said and how. Maybe the footer is a wild space where there is more room to roam and wander, to chase the rabbits and squirles we encounter along the carved path of the narrative above? Maybe the footer is more like a swirling or buzzing foundation that grounds the very possibility of the narrative body, than a container for leftover, extra, or nonessential adornments to a self contained text? What if these groundling musings actually bubble up, spill over and release possibilities into the page rather than catching the droppings that get trimmed or cooked off in the writing process? Could we read Benjamin’s Arcades Project as writing only in footnotes?) to the bottom margin be moved into the ‘body’ space of the text? Should they still remain set apart? If so, how, spatially? Inset boxes, indents, style, pop up callouts, links to other pages?

This paragraph above performs the very question we are exploring magnificently. In this otherwise than print medium, what might we do with the long parenthetical remark that fills a majority of the paragraph and splits a sentence into distant halves? What are the possible ways to provide readers more contact with the mention of Benjamin’s Arcades? What does the place-ment of these fragments suggest about their role in the meaning possibilities of the project?