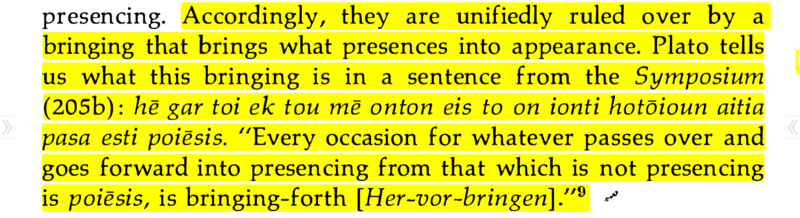

The quote I referenced in troubling poiesis from William Lovitt translating Martin Heidegger translating Plato in “The Question Concerning Technology,” p. 10, offers a beautiful example of translation enacting an anarchic poiesis.

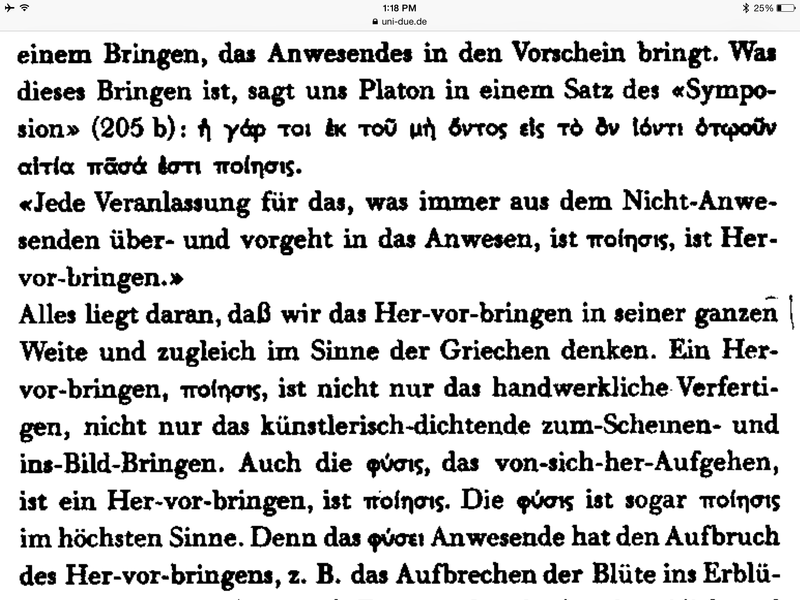

In the highlighted fragment above, we have an english translation of what was initially published in German (let’s assume Heidegger wrote in German). The passage includes an untranslated sentence of Greek from Plato and then offers a translation. The English text seems to indicate that the translation of the sentence from the Symposium was from Greek to German and then German to English. Could Lovitt simply have translated the Greek to English? When Lovitt translates Heidegger’s translation, is he translating Heidegger or Plato or both? Does it matter?

In the highlighted fragment above, we have an english translation of what was initially published in German (let’s assume Heidegger wrote in German). The passage includes an untranslated sentence of Greek from Plato and then offers a translation. The English text seems to indicate that the translation of the sentence from the Symposium was from Greek to German and then German to English. Could Lovitt simply have translated the Greek to English? When Lovitt translates Heidegger’s translation, is he translating Heidegger or Plato or both? Does it matter?

These possessive qualifiers for translations signal the difficulty of the very ideas of anarchy and palimpsest. I call the German translation of Plato here Heidegger’s, only because it appears in a published work attributed to Heidegger without any indication that the translation is from another source. That said, we could imagine any translation as a conversation with other possible translations, explictly available or not.

Lovitt chooses to ‘presence’ one important German word in the English translation of the German translation of the Greek. This ‘appearance’ of Her-vor-bringen in Lovitt’s translation of Heidegger’s translation of Plato signals both that Lovitt is indeed working with Heidegger’s German translation of Plato and enacts a connection to the materiality of the German language. Perhaps this is Lovitt imitating Heidegger’s methodology in small part? Heidegger too included the Greek quote from Plato which offers a way of materially signaling a connection between this Greek tradition and his own use of the term. Interestingly, ποιησις remains in the German text, glossed by the addition of Her-vor-bringen at times, but not simply translated (Heidegger, Die Frage nach der Technik, 11).

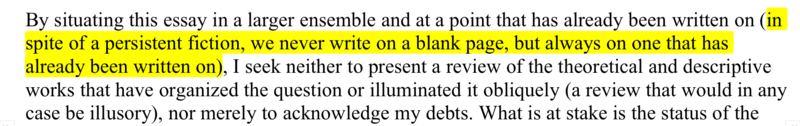

This material connection between the lexemes from multiple languages signals the palimpsestuous process of translation, where previous uses of the page are erased and written over, but the erasure is never complete. The Greek and the German still haunt the pages of Lovitt’s English translation. Steven Rendall translating Michel de Certeau in the discussion of scripture in The Practice of Everyday Life, p. 43, pushes the notion of palimpsest toward simulacrum by suggesting that we never begin with a blank page:

This material connection between the lexemes from multiple languages signals the palimpsestuous process of translation, where previous uses of the page are erased and written over, but the erasure is never complete. The Greek and the German still haunt the pages of Lovitt’s English translation. Steven Rendall translating Michel de Certeau in the discussion of scripture in The Practice of Everyday Life, p. 43, pushes the notion of palimpsest toward simulacrum by suggesting that we never begin with a blank page:

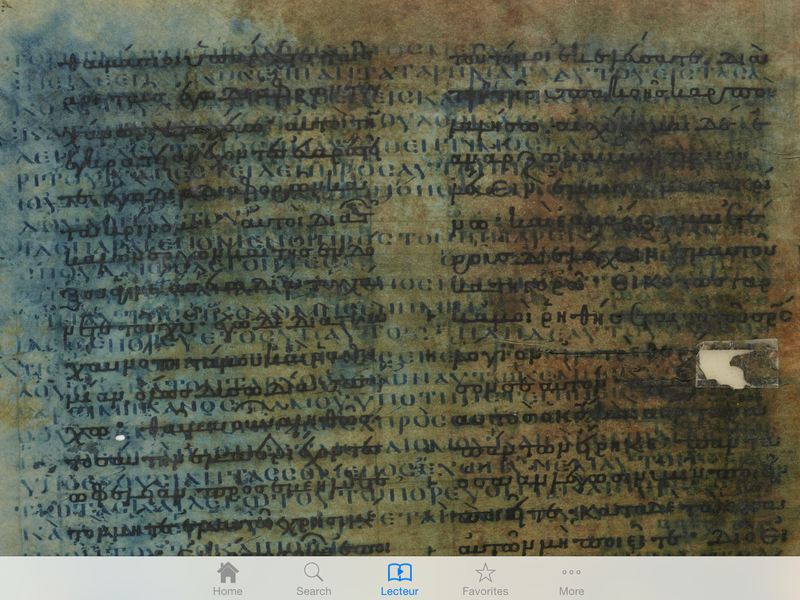

Perhaps one way to describe the operations of simulacrum is through the notion of anarchic palimpsest, a writing over that has neither beginning nor end, an infinite process of re-use that questions the ideas of source and target, copy and original. Below is an image of a page from Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus, a fifth century manuscript of biblical texts in Greek, washed and written over in the 12th century with Greek translations of the fourth century Syriac writings of Ephrem the Syrian (the wikipedia entry on Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus is excellent and provides significant references for a deeper look at the manuscript). Does this beautiful material enactment of palimpsest, two column miniscule Greek translations of Syriac over single column uncial Greek biblical texts, suggest anything to us about the process of translation itself?

Perhaps one way to describe the operations of simulacrum is through the notion of anarchic palimpsest, a writing over that has neither beginning nor end, an infinite process of re-use that questions the ideas of source and target, copy and original. Below is an image of a page from Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus, a fifth century manuscript of biblical texts in Greek, washed and written over in the 12th century with Greek translations of the fourth century Syriac writings of Ephrem the Syrian (the wikipedia entry on Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus is excellent and provides significant references for a deeper look at the manuscript). Does this beautiful material enactment of palimpsest, two column miniscule Greek translations of Syriac over single column uncial Greek biblical texts, suggest anything to us about the process of translation itself?

(Image of Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus 1v (view 15) taken from iOS app Gallica by Bibliothèque nationale de France.)

(Image of Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus 1v (view 15) taken from iOS app Gallica by Bibliothèque nationale de France.)

Each of these quotes and images has so much going on and could offer endless moments for conversation. I won’t pretend to do these writers or these texts a kind of totalizing justice (or is it an injustice?) by providing any comprehensive read or contextualization. Here, methodologically, we enact a simulacrum, a palimpsest, where we ‘write upon’ the method of literary montage offered by Benjamin in his Arcades Project. We will simply read these bits alongside one other and see what we make.