As an academic and a technologist, I have spent much of my career negotiating the legal and financial demands of copyright and licensing. Collaborative and open community sourced projects in the technological realm such as Ubuntu Linux, Moodle LMS, and Python, along with open access movements in the sciences (PLOS) and the humanities (OHP) have always been a draw for me. Early on, I developed a largely uninformed and strangely visceral commitment to the eradication of copyright and software licensing. Then, without knowing anything about the Creative Commons movement, I accidentally wandered into a keynote address at the 2009 EduCause gathering in Denver, where Lawerence Lessig made an utterly compelling case for what I now would call a new media translation of copyright, rather than its abolition. Here is a short excerpt from that keynote (for full keynote see Educause mediasite):

These questions about incentivizing innovation, the meaning of ‘use,’ and protecting rights while encouraging collaboration, still bother me today. When I began considering the idea of making my dissertation in a public space on the internet, Lessig and the Creative Commons movement gave me a way to imagine an appropriate licensing model for this medium. You can see some of my early discussions of open access and licensing for a proximate bible in difficult openness and author-ity. In all of this discussion, I have not been able to shake a brief conversation I had over dinner with a scholar I respect deeply about the risks of approaching a dissertation in public web space. This scholar asked me two things: 1) how would I demonstrate my original scholarly contribution in the work and 2) how would I navigate access embargoes typical of print dissertations? My committee has helped me reflect on how my initial negative reactions to both of these questions could be a performance of my privilege as a white, male, heteronormative, western educated, non-tenure track bound doctoral student.

On one hand, with the notion of palimpsest, I am committed to questioning the assumptions of the singular, isolated, and originary author operative in the scholarly realm. For example, how do we determine someone’s original authorial contribution in a print published book if we accept the idea that there is never a blank page as discussed in reading interfaces? Is it the authorial name inscribed on the cover of a book and the unquoted lines of the manuscript? Where do the voices of those who have influenced our thinking begin and end when we write? On the other hand, am I only willing to ask this question because of an ingrained assumption that I will be included in the discourse of my guild and my institution even without needing the cultural capital of authorship? Does the capital that I carry in my body and my heritage lead me to assume that my voice will not be erased or dismissed? If so, are there ways we can continue to problematize the notions of singular originality as the mark of meaningful scholarship, while still advocating for the cultural capital of authorship as a means of interrupting the excluding and homogenizing tendencies of many discourses? Or, as this tweet suggests, do many forms of academic authorship ask people to perform as white male?

I’m so glad that people are saying this more and more loudly. @modelviewculture https://t.co/prrrqHYaSm pic.twitter.com/8vKn63LJwD

— Mar Hicks (@histoftech) December 14, 2015

Perhaps the Creative Commons (CC) licensing options can offer some shifts in our assumptions about authorship? I am changing the CC license of a proximate bible to suggest a media translation of authorship that enacts a partial erasure and writing over of the cultural idea of author, without the need to eradicate it. I began this project with an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike (BY-NC-SA) CC license. Lessig introduces each of these options in the short clip above and you can learn more about the layers of licenses and what each option entails from Creative Commons. Below are my reflections on each part of the license and why I am keeping them or not.

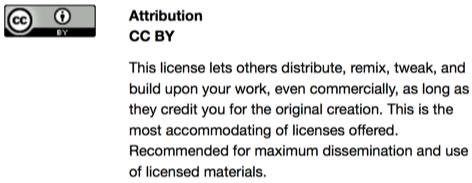

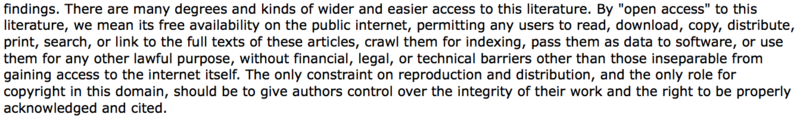

Attribution (BY) is the most basic CC license available. Following the 2002 Budapest Open Access Initiative, many (i.e. PLOS and SPARC) see this CC BY license as the marker of the open access movement. You can see the commitment to minimizing barriers to access that promotes the CC BY license as preferred in this excerpt from the Budapest Initiative:

I’m not sure what they might have meant by ‘give authors control over the integrity of their work’ when the attribution license allows for remix and reuse without regulation. Perhaps, the requirement for attribution allows for an ongoing conversation among layers of the palimpsest that is any work?

Though I am still uncomfortable with the notion of singular author/scholar propogated by this attribution license, I am compelled to keep the BY portion of the license for three reasons:

-

As my friend and colleague Debbie Creamer has taught me, attribution can provide avenues for new conversation partners and can afford connections that may not be possible without having a name associated with a work. This need not suggest that attribution requires the idea that an ‘author’ is the sole originator or creator of a work. Rather, what if we imagined attribution as indicating the person taking responsibility for this moment in the life of a palimpsest? One way I gently resist the singular/isolated author idea is the change in language on my post header in a proximate bible from ‘Published by Michael Hemenway’ to ’Curated by Michael Hemenway.’ This may seem like an insignificant semantic difference, but I hope it signals that I take full responsibility for my role in this space of dialog and inquiry, yet I am decidedly aware that my contributions are always entangled with and dependent on many others.

-

As mentioned above, encouraging the practice and protection of attribution allows creative works the opportunity to provide a means of cultural capital. Though this is far from enough on its own to challenge the tendency toward a homogenizing dominance of certain voices, hopefully it can continue to offer one avenue of difference. Yet, how can media translations of authorship address the concerns raised by Amy Nguyen in the tweet mention above of her essay, ’The Pie is Rotten:Re-evaluating Tech Feminism in 2016.’

-

The demand for attribution promotes the possibility for a kind of contact without grasp (by grasp here, I mean a totalizing consumption or assimilation). One of the reasons I often use images of texts taken from my screen or from a print codex as the medium for quotes in a proximate bible is to remind us that these voices come from elsewhere. Attribution can foreground the collaborative encounter that is writing/making and interrupts our tendency to assimilate other voices into our own.

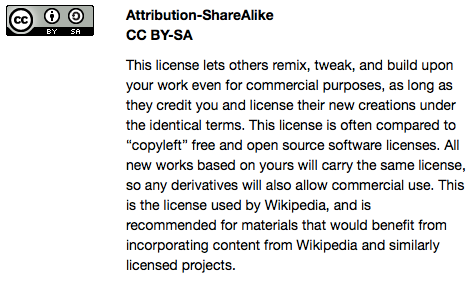

This CC license adds the ShareAlike (SA) requirement to the Attribution license. As noted above, this requirement is NOT typically considered necessary for open access works. I considered leaving the SA requirement out of the license for a proximate bible to follow the open access guidelines of organizations like PLOS and SPARC. Yet, technologies, laws, and licenses have the potential to shape different dispositions in people. One way to encourage a culture of sharing resources with fewer barriers is to build the demand for sharing into the licensing. An open permission for use and remix should come with a demand to share whatever is made in a similar manner in order to sustain the culture of open access. A great deal of the world’s innovative software over the last few decades has emerged from community sourced projects under GNU General Public Licensing, which supports this ‘copyleft’ approach. A commitment to sharing as well as access builds a culture of creativity that can sustain itself collaboratively.

From my work in bible and material book culture, I think of this ShareAlike component of the CC license as a celebration of the palimpsest or an invitation to participate in the life of a manuscript that never reaches a stable final form. By asking people who might want to ‘use’ or participate in my palimpsestuous work to share their own palimpsests in similar ways, we are creating a sustainable space for tactical consumption in de Certeau’s terms, the infinite poiesis that is the practice of everyday life. What if bible translations embraced a CC BY-SA license? How would this transform the cultural iconicity of bible and its reading practices?

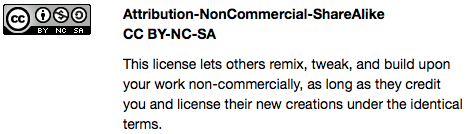

The CC BY-NC-SA license is the default license we use at Iliff School of Theology for all of our online course materials and design. Instructors can choose to tighten or loosen this license, but this is the place we begin. In addition to the BY-SA components discussed already, this license adds the NonCommercial (NC) restriction, which prohibits others from making money on any use/remix of a work. Given the anxieties about intellectual property and the growing attempts to monetize online learning modules, I think it makes sense to protect instructor designed courses in this way. This is also the license that I began with on a proximate bible, partially in response to the print embargo question raised by the visiting scholar I mentioned above. Here is a snapshot of the old footer on the site:

Whether to keep this NonCommercial (NC) component in the CC license for a proximate bible remains a difficult decision for me. We have a history of exploitation in the academy and in technology, where some people are willing to make a profit (both monetary and social legitimation) at the expense of others, without acknowledgement of or compensation for their work. Could a restriction on commercial use of a work curb this tendency toward exploitation? Is it equally as likely in this new media age, when content is so easily acquired and rebranded, that a NonCommercial barrier could incentivize the reuse of a work WITHOUT any attribution at all?

At this point in my process (perhaps as a product of my privilege), I am more interested in lowering barriers to the palimpsestuous nature of making afforded by our present new media landscape than I am in protecting my theoretical potential (though practical unlikelihood) for commercial revenue. If someone finds a way to monetize a remix of my curative work, I want to encourage them, while still asking to be included as a part of the conversation (Attribution) and asking them to share their work in similar ways for others (ShareAlike). So, by dropping the NC component in the CC license for a proximate bible, I am supporting the open access value of lowering barriers to use/remix of resources. Yet, I retain the SA aspect of the license in hopes of encouraging a sustainable palimpsestuous disposition in our culture of collaborative making. You can see my new CC BY-SA license specifications in the footer of every page of the a proximate bible space.

Thanks to postach.io for making it so easy to customize themes with changes like this license update in my site footer. Thanks also to Roger Dudler for his fantastic simple guide to git.