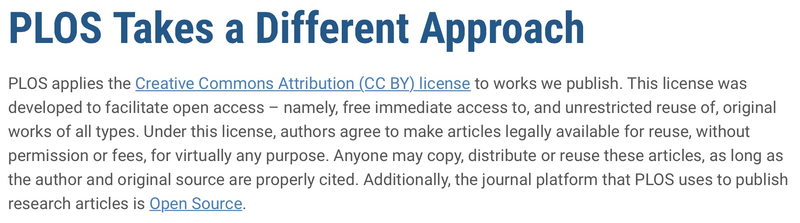

I’m considering changing the Creative Commons license on a proximate bible to signal even more investment in the open access movement. PLOS (Public Library of Science) is one of the major champions and practitioners of open access in the academy. Below, I engage their statement of commitment to open access. All excerpts taken from the PLOS website.

According to the PLOS approach, is the composition below an original work or a reuse? How would we decide?

This assumes that payment was primarily about material access to content even for print. Yes, each print artifact probably costs more than a digital artifact to reproduce, but perhaps the economics of use has as much to do with legitimation and incentive as material costs. If material costs were the issue, many more people would be exploiting the low cost, high volume delivery mode of the internet; e-books and online journals would be incredibly cheap. But they aren’t.

This assumes that payment was primarily about material access to content even for print. Yes, each print artifact probably costs more than a digital artifact to reproduce, but perhaps the economics of use has as much to do with legitimation and incentive as material costs. If material costs were the issue, many more people would be exploiting the low cost, high volume delivery mode of the internet; e-books and online journals would be incredibly cheap. But they aren’t.

If an open access movement is going to champion unrestricted (re)use of content, what role does attribution play? Perhaps the residual of licensing and authorship and ownership retain the incentive for innovation through recognition? Or does attribution play a central role in tracing conversation networks and curation of resources? In this ideology of open access, why license at all? How is the notion of ‘original work’ even useful in this framework?

If an open access movement is going to champion unrestricted (re)use of content, what role does attribution play? Perhaps the residual of licensing and authorship and ownership retain the incentive for innovation through recognition? Or does attribution play a central role in tracing conversation networks and curation of resources? In this ideology of open access, why license at all? How is the notion of ‘original work’ even useful in this framework?

How do we distinguish between use and reuse? Maybe this is simply pedantic semantics, but in these times of internet access to content and materials, is not every use an act of production or even a claim on ownership?

If open access movements are interested in shaping the dispositions of our next generation of scholars, why wouldn’t we use a CC BY SA license (Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike license) as the standard for open access? The CC BY SA license provides free and open access, maintains the cultural capital of authorship and ownership, and encourages user/producers to propagate the practice of open sharing in the infinite poiesis that is use.

I fully advocate faster timeframes for sharing ideas and generating conversation around suggestive work, but does open access really address the issue of acceleration? If creators or institutions are using embargoes or other restrictions on access to protect economic possibilities in the print publishing world, then open access mechanisms may enhance the speed of access to information. Yet, even open access platforms like PLOS have intricate legitimation and quality control processes that slow access to information and ideas every bit as much as the economic licensing structures. Open Access approaches provide broader access, which is a wonderful thing, but not necessarily faster access. To facilitate accelerated access and discovery, we would need to change the editorial and vetting processes. What cultural shifts are needed to share research and ideas more widely earlier on in the creative process as a part of the legitimation process? Why do scholars like me spend more time questioning and critiquing open access resources like Wikipedia than we do participating in them?

I fully advocate faster timeframes for sharing ideas and generating conversation around suggestive work, but does open access really address the issue of acceleration? If creators or institutions are using embargoes or other restrictions on access to protect economic possibilities in the print publishing world, then open access mechanisms may enhance the speed of access to information. Yet, even open access platforms like PLOS have intricate legitimation and quality control processes that slow access to information and ideas every bit as much as the economic licensing structures. Open Access approaches provide broader access, which is a wonderful thing, but not necessarily faster access. To facilitate accelerated access and discovery, we would need to change the editorial and vetting processes. What cultural shifts are needed to share research and ideas more widely earlier on in the creative process as a part of the legitimation process? Why do scholars like me spend more time questioning and critiquing open access resources like Wikipedia than we do participating in them?

More than accelerating discovery, I see the open access movement offering an opportunity to foreground and teach the complex and tortuous process of discovery. Give people a window into the incremental, iterative, and error riddled journey that is research and writing. Encourage creators to share their work in what many would consider draft form, with questions still remaining and gaps unfilled. In what ways has print and the academy it spawned conditioned us away from this kind of openness and vulnerability? This approach adds more layers to the notion of openness in open access and has the potential to reinvigorate collaborative curiosity and risk in the innovative process instead of the caustic and isolated anxiety that characterizes so much of today’s research frontiers.

I agree that education stands to encounter fantastic opportunities from open access initiatives like PLOS. If we will have access to more and more recent research and ideas, what capacities do we need as learners to curate this work, to make selective choices about the work that both informs and challenges our inquiry best? If open means more than just consumption of information free of charge, how do we cultivate dispositions of use as participatory production? The responsibility and vulnerability of this approach is a difficult openness.

A friend pointed me toward this Facebook post today by Vicente Rafael. Rafael offers us a beautiful picture of a difficult openness that foregrounds process in vulnerability, which opens possibilities for conversation and engagement. What cultural dispositions create the need for him to qualify that his reflections are in draft state? Are we not always in draft state?