This is a continuation of proliferation of faces, which began a conversation about the possibilities of faces in online interactions and questioned the operations of the phrase ‘face-to-face.’

The affordances of the technologies I am using to make this project would allow me easily to update and add to the proliferation of faces entry. I have decided to compose a new entry, not to preserve the stability of the previous conversation in any way, but to offer another point of contact with that conversation, without getting buried in the content of the previous entry.

I appreciate academics who change their mind and talk about it. I learn so much from people who share their process of change by staying engaged in a dialog. Sherry Turkle is one of these thinkers. Turkle has become a prominent public voice in discussions of technology and its social effect, as evidenced in the impressive attention captured by her new book, Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age.

I attempted to embed a storify story here for a more media rich engagement with the discourse around this book, but the storify embed fails to load on iOS browsers, so I have opted for just the link on ‘impressive attention’ above.

I first encountered Turkle’s work while engaging a Richard Cohen article, ’Ethics and Cybernetics: Levinasian Reflections,’ in my struggle with the face to face language in online education. Using her work from 1995, Life on the Screen, Cohen offers Turkle as an example of media scholars who champion the advantages of cybernetics and internet communication technologies for redefining subjectivities in the direction of post-modern notions of multiplicity and instability (Cohen, ‘Ethics and Cybernetics,’ 27, n. 2). As mentioned in the NPR interview above, Turkle’s more recent work (e.g. Alone Together and Reclaiming Conversation) has shifted focus from this earlier celebration of the fragmented self to a serious anxiety about the effects of robotics and mobile devices on our social capacities as humans.

Two minutes into the NPR interview embedded above, Turkle suggests that ‘face to face conversation is the most human and humanizing thing that we do, it’s where we learn to put ourselves in the place of the other.’ Admittedly, I am unnaturally sensitive to the phrase ‘face-to-face’, especially when posed as a binary to digital conversation. So, it is no surprise that the title of the NPR conversation with Turkle, “Making the Case For Face to Face in an Era of Digital Conversation,” caught my attention.

Two notes here and an aside (within an aside). Aside: I am still unsure about the criteria I use to decide what goes in a note like this and what stays formatted as ‘normal’ text. First, this interview with Turkle is fascinating because it occurs in a studio, with Scott Simon and Sherry Turkle enacting the values espoused by her latest book by talking to one another ‘face-to-face.’ Yet, the interview is made available via digital technologies on NPR’s website. Second, if you hadn’t already noticed, the title of this post is a mashup of Turkle’s new book title and the NPR interview title. In a sense, the question I am after in this entire a proximate bible project is whether digital technologies afford us the conditions of possibility for a Levinasian face-to-face?

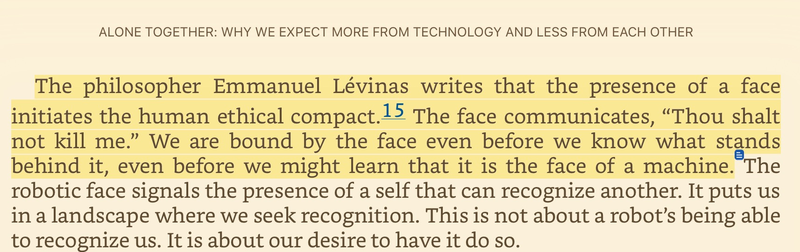

In both Alone Together, 137,

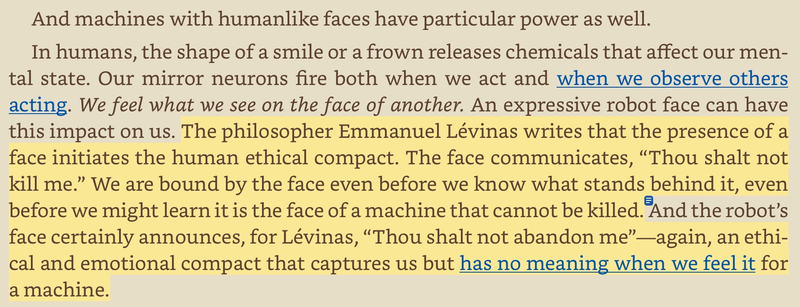

and Reclaiming Conversation, 342,

and Reclaiming Conversation, 342,

Turkle draws on Alphonso Lingis’s translation of Levinas’s discussion of ‘Ethics and the Face’ from Totality and Infinity (TI) in her analysis of robot-human interactions. Here are a few pertinent bits (pun intended) from this section out of Lingis’s translation of TI:

Turkle draws on Alphonso Lingis’s translation of Levinas’s discussion of ‘Ethics and the Face’ from Totality and Infinity (TI) in her analysis of robot-human interactions. Here are a few pertinent bits (pun intended) from this section out of Lingis’s translation of TI:

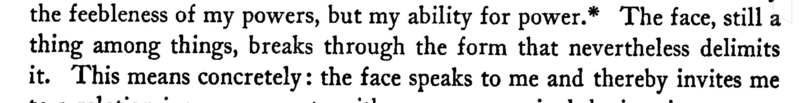

Here we begin to hear what I have been calling a difficult materiality of the face, where the face is a thing, while at the same time, exceeding its thingness (TI, 198).

Here we begin to hear what I have been calling a difficult materiality of the face, where the face is a thing, while at the same time, exceeding its thingness (TI, 198).

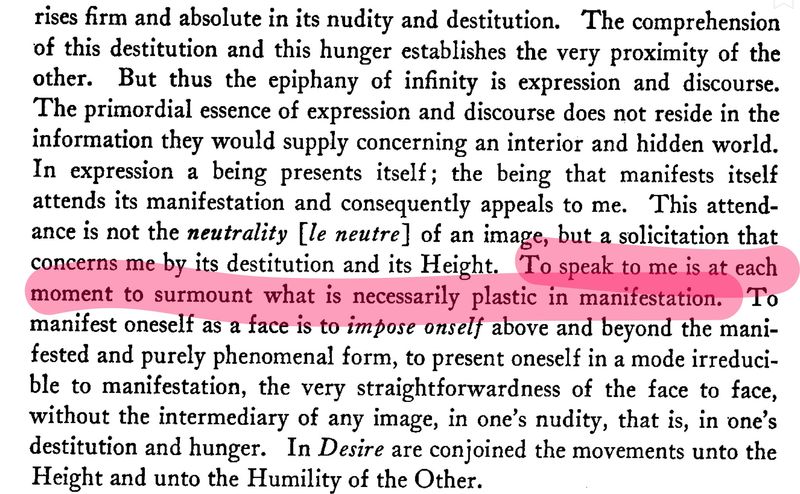

This passage (TI, 200) reminds us of some of the crucial terms (in English translation) in Levinas’s discussion of the encounter with the face, namely, infinity and proximity. We will not unpack these terms here, but it is important to remember that this discussion of the difficult materiality of the face is deeply connected to the operations of infinity and proximity throughout his work.

This passage (TI, 200) reminds us of some of the crucial terms (in English translation) in Levinas’s discussion of the encounter with the face, namely, infinity and proximity. We will not unpack these terms here, but it is important to remember that this discussion of the difficult materiality of the face is deeply connected to the operations of infinity and proximity throughout his work.

The pertinent part of this passage for our discussion here is the bit just below the highlight. In the quotes above from Turkle’s books, we hear ‘the presence of a face initiates the human ethical compact.’ Yet, this passage from Totality and Infinity suggests that this ‘presence’ of the face is not a simple manifestation, but instead exceeds ‘what is necessarily plastic in manifestation’ and goes ’above and beyond the manifested and purely phenomenal form, to present oneself in a mode irreducible to manifestation.’ (emphasis my own). Encountering the face is presence otherwise.

Thanks to Sarah Pessin for this phrase ‘presence otherwise,’ which is a play on Alphonso Lingis’s English translation title of Levinas’s second major philosophical work, Otherwise Than Being. Pessin has helped me see that in English, ‘presence otherwise’ does a better job of maintaining presence as a part of this encounter with the face, even as the face exceeds any notion of presence we might be familiar with. The face does not oppose or negate presence, but exceeds it, thus ‘paralyzing the power of power’ (TI, 198).

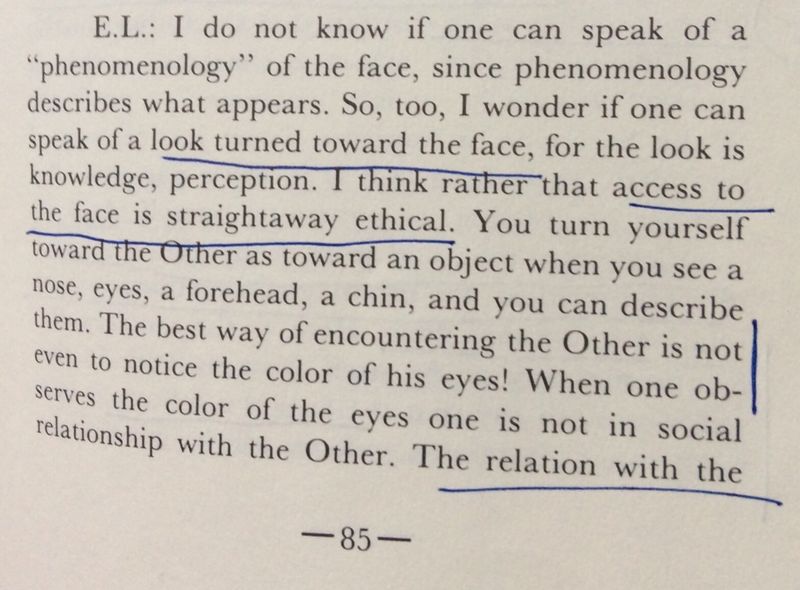

An easy target here for those worried about the impact of recent technologies on human encounter is the idea of ‘…the very straightforwardness of the face to face, without the intermediary of any image…’ (TI, 200). From this, we might conclude that some kind of unmediated vision is the only access to the face, particularly with the reference to ‘nudity’ in the same sentence. Yet, if the encounter with the face is a presence otherwise and a contact without grasp, then perhaps perception and knowledge of the face are just as mediated by images as SMS, facebook, twitter and the rest? As highlighted in proliferation of faces, looking at the face may not be the primary mode of ethical encounter (Cohen translating Levinas, Ethics and Infinity, 85).

Human interaction is mediated by technologies broadly defined, from language and perception in the physical realm to screens and bytes in the digital realm. So, when we compare an encounter in flesh to one via a digital technology like SMS, we are not dealing with the difference between unmediated and mediated encounters, respectively, but simply differently mediated encounters. If we can also agree that media technologies are not neutral, contra Richard Cohen in ‘Ethics and Cybernetics,’ then we are left with a question about the capacity for certain material media environments (e.g. the body and the internet) to host the possibility of the face-to-face, or ethics.

Human interaction is mediated by technologies broadly defined, from language and perception in the physical realm to screens and bytes in the digital realm. So, when we compare an encounter in flesh to one via a digital technology like SMS, we are not dealing with the difference between unmediated and mediated encounters, respectively, but simply differently mediated encounters. If we can also agree that media technologies are not neutral, contra Richard Cohen in ‘Ethics and Cybernetics,’ then we are left with a question about the capacity for certain material media environments (e.g. the body and the internet) to host the possibility of the face-to-face, or ethics.

I look forward to more conversation here with S. Brent Plate’s idea that the senses are the media of the body and how this might overlap with the difficult materiality of the face (see Plate’s ’The Skin of Religion’).

Our discussion here of the face to face in Levinas has focused on the relationship we have to communication technologies like sight, knowledge, perception, SMS, email, and social media. In her books, Turkle invokes Levinas and the face to face as a part of her discussion about human intimacy with and attachment to robots. Our emotional expectations of robots as artificial intelligence becomes a more prevalent part of our lives is an important issue, but not my primary focus here. Yet, in the NPR interview that spawned this discussion, Turkle invokes the notion of ‘face to face conversation [as] the most human and humanizing thing that we do,’ in response to Scott Simon’s joke about iPhones and their impact on human interaction, not as a comment on our relationship with robots. Undoubtedly, technologies like an iPhone or a microphone or glasses or hearing aids will impact and shape the space and performance of human interaction. Yet, as we have discussed above, the face to face conversation that Turkle is trying to reclaim turns out to be just as mediated with respect to the presence otherwise of the face as is texting or twitter. Can we then imagine the possibility of reclaiming face to face in digital technologies such as SMS, twitter, or discussions in online course? Even further, is it possible that some of these emerging digital communication technologies and the strange/strained material presence they enact could shape a growing disposition in us toward the humanness of presence otherwise?

I recently went back and watched Sherry Turkle’s Ted Talk from 2012. So many wonderful things to engage in this Ted video, not least the paradox of the polished form of the Ted lecture espousing the values of messy interpersonal communication.

Turkle begins the video with the story of her own journey from the cover of Wired magazine, excited about the possibilities for emerging technologies to shape the way we imagine our selves, to her social critique in Alone Together of the ubiquity of mobile devices and the rise of companion robots. Turkle is not alone in her concern about emerging technologies and stands in a long tradition with the likes of Plato, Heidegger, and Nicholas Carr, to name just a few. Yet, the two most interesting parts of this Ted talk for our discussion of face to face in digital conversation are

- What are the connections and disjunctions between mobile communication technologies like SMS, twitter, snapchat, instagram, etc. and relating to robots? Is this transition a matter of degree or are these two types of interactions different in kind?

- Is Turkle advocating conversation (as opposed to connection in her language) as a kind of metanarrative in contrast to the petit récit of connection via fragmented tweets and texts? Can the complicated relationships between speech and writing give us any insight into the respective amounts of control we have in ‘presenting’ ourselves in the flesh vs. online? Could it be that the illusion of control in the online/asynchronous connection sphere is a new media translation of the reign of authorial intent?